nba: how does the rise of the 3-pointer impact offensive rebounding strategy?

Aug 17, 2018 · 9 minute readTLDR: Teams that play “Morey-Ball” should value offensive rebounds more, and consider devoting more resources to grabbing them.

Rebounding is fairly valuable in basketball, as a rebound results in additional possession (worth over 1 point). With points per possession increasing league-wide as a result of the NBA’s recent 3-point revolution, why, in fact, are offensive rebounding numbers dropping to all-time lows?

In this post we are concerned with the following strategic questions:

- How should teams strategize offensive rebounding? What information do we need to help us make this decision?

- What constitutes strategizing? Sending more (or less) people to go after offensive rebounds? Valuing rebounding more (or less) in player evaluations? Knowing when to go after offensive rebounds, and when not to?

- How much are offensive rebounds worth? Are they worth more depending on where you shoot from?

- How should offensive rebounding strategy change depending on style of play? In particular, what should offensive rebounding strategy be for 3-point shooting teams?

Unlike some other posts, this blog post won’t feature my own work extensively. Instead, I hope to summarize outside literature and combine it with some minor work of my own.

Introduction: The State of Things

The NBA has witnessed an analytics-driven trend towards shooting more efficient (higher expected value per attempt) shots - namely 3 point shots, 2 point shots close to the basket (dunks, layups), and free throws.

Take the Rockets and GM Daryl Morey, for instance. Known for their ‘Morey-Ball’ tactics, in the 2017-2018 NBA season, the Rockets shot 3’s at the league’s highest frequency(52.6%). The Rockets paired that with the league’s highest field goal percentage for 2-pointers (61.9%). In other words, they limited their 2-point attempts to only the most efficient shots.

An increase in offensive efficiency increases the value of an offensive possession (i.e. increased points per possession). This, then, suggests an increase in the value of an offensive rebound, where an offensive rebound results in an additional possession for the offense.

However - over the last 5 years, the offensive rebound rate (percentage of missed shots resulting in offensive rebounds) has decreased each and every year.

The offensive rebound rate was 22.3% for the 2017-2018 NBA season, an all-time low since offensive rebounds were first tracked in 1963.

The argument coaches have been presenting against offensive rebounds is that they are risky, and make you vulnerable on the defensive side - especially against these new sniper-happy Warriors / Rockets - esque teams. Many prominent NBA coaches such as Greg Popovich, Doc Rivers, and Erik Spoelstra have been on record denouncing the value of offensive rebounds.

Offensive Rebound Valuation (Intuition and Logic)

Is an offensive rebound really worth more as teams improve their points per possession?

Consider a team like the Rockets. Assume league-wide, teams average 1 point per possession. Next, suppose the Rockets, with their newly minted Moreyball offense, improve to 1.2 points per possession. Then, an offensive rebound must then be worth more to the Rockets than it previously was. To see why, consider an extreme case: if the Rockets suddenly averaged 10 points per possession, they would go crazy after offensive rebounds, right?

However, an increase in points per possession alone does not always mean an offensive rebound is worth more. Consider if every team in the NBA, bolstered by the 3-point revolution, increased its points per possession to 2 (impossible, but let’s assume so for the sake of clean numbers).

This, then, is simply ‘point inflation’ - it’s as if the NBA made each 2-pointer worth 4, each 3-pointer worth 6, and each free throw worth 2. The value of a possession, or an offensive rebound, does not rise.

In summary: an offensive rebound’s value increases as your relative offensive efficiency increases. Perhaps counterintuitively, this means offensive rebounds should be worth more against teams with bad offensive efficiency than against teams with good offensive efficiency. If your team averages 1.1 points per possession, it should value offensive rebounds more against a team averaging 1.0 points per possession than against a team averaging 1.2 points per possession.

This, then, supports the arguments posed by Popovich and co. - when playing against the Warriors and Rockets, offensive rebounds indeed have less value, since against those teams, relative offensive efficiency is low. However, perhaps the coaches might reconsider being more aggressive on the boards when against teams with poor(er) offensive efficiency.

Offensive Rebound Valuation (Data)

In practice, offensive rebounds are worth even more than the regular possession, since on possessions after offensive rebounds defenses may not be as prepared to defend

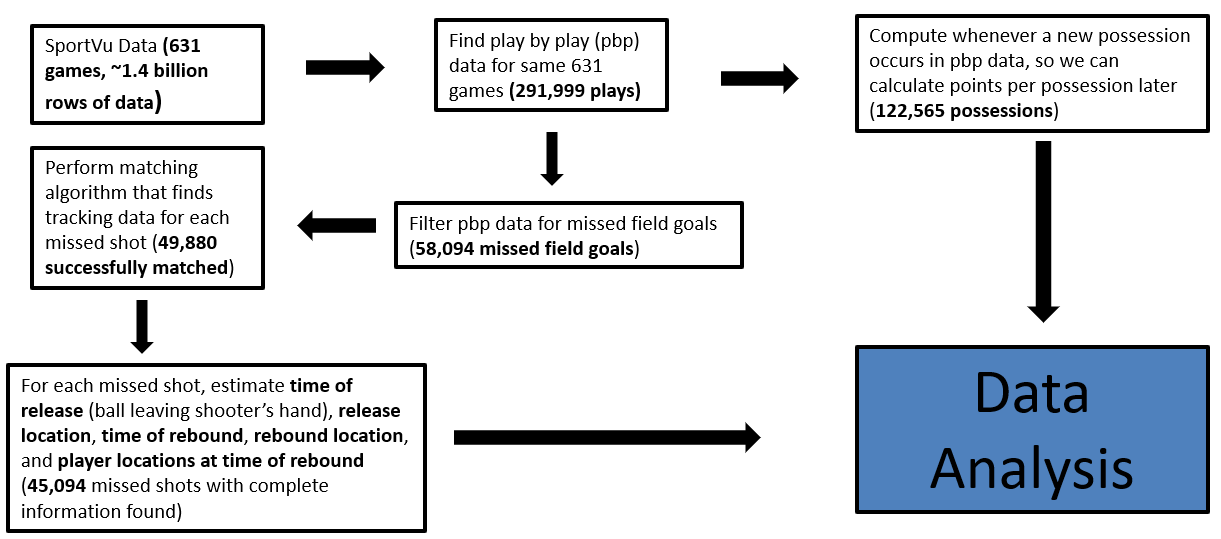

Using publicly available SportVU tracking data from 631 games in the 2015-2016 NBA season and publicly available play-by-play data from NBA.com, I calculated points per possession for possessions after offensive rebounds. Below is the data pipeline:

And here are the results:

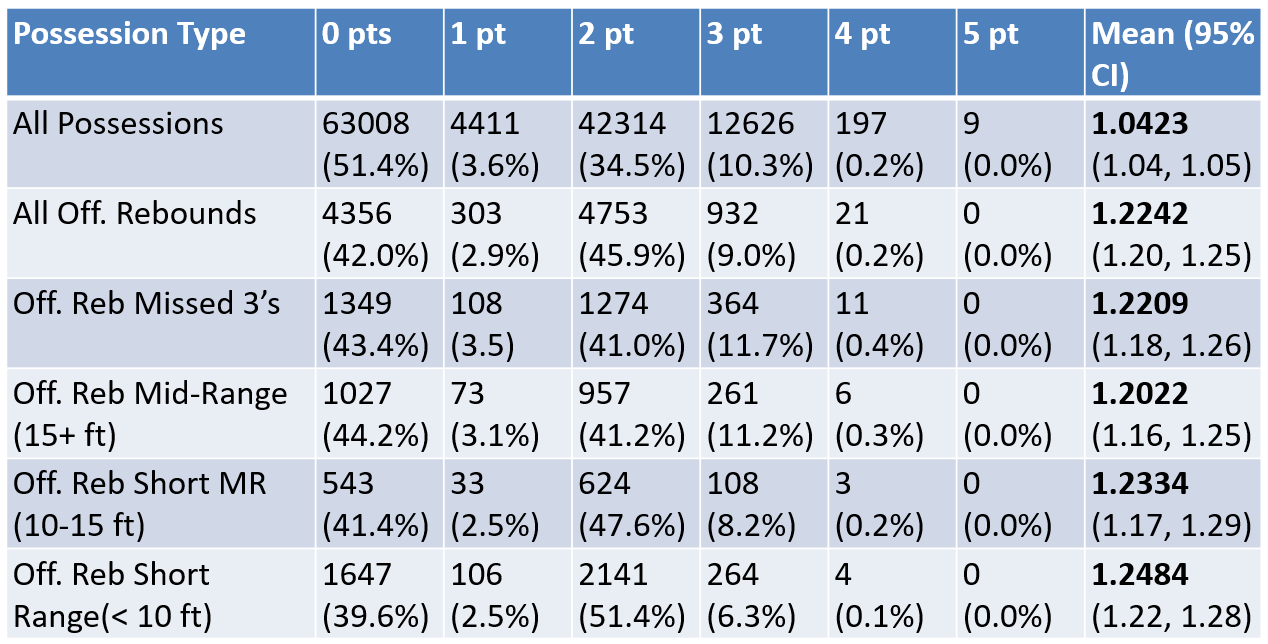

The chart includes six different types of possessions. First, there’s all possessions. Then, all possessions coming off offensive rebounds. The final four groupings are subgroupings of possessions coming off offensive rebounds - differing based on where the missed shot that led to the offensive rebound was shot from - i.e. offensive rebound possessions off missed 3’s, offensive rebound possessions off missed close shots, etc.

For each possession type, the chart shows how often possessions of that type end up in 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 points. The final column shows the average points per possession for that possession type.

As of the 2015-2016 season, points per possession is higher for possessions coming off offensive rebounds (1.2242 to 1.0423), and this difference was statistically significant (p < 2.2e-16).

The points per possession for offensive rebound possessions also varied by missed shot location, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Depending on where the missed shot was taken from, the outcome of the possession afterward differed. For instance, we might expect a missed layup to more often result in a put-back, whereas we might expect a missed three-pointer to more often result in a reset (i.e. restart the offense and run a set). These notions are supported by the data; possessions off missed short-range (< 10) shots had the highest chance of ending in two points (i.e. putback), lowest chance of ending in 0 points, and lowest chance of ending in 3 points.

The ‘differences’ in possession outcome (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 points) were statistically significant (chi-squared test) between missed 3PT offensive rebound possessions and missed close-range offensive rebound possessions.

Crashing the Boards: A Case of Risk Aversion?

Devoting resources to offensive rebounds has an obvious tradeoff, as noted by coaches around the league: if you fail, you make yourself vulnerable on the defensive end. Luckily, this sort of thing can be modeled with classic risk / reward modeling.

In 2013 MIT Sloan Paper “To Crash or Not to Crash”, Wiens et. al measured the expected ‘value’ of the next possession depending on how many offensive players ‘crashed’ (went after) boards.

First, the study found that, yes, there is a positive correlation between sending more ‘crashers’, and offensive rebound rate. More sigificantly, the study concluded, “focusing on the offensive rebound immediately after the shot goes up seems to trump the gain a team gets with a head start on getting back” (I’m leaving out a lot of specifics - the methodology and specific results in the paper are quite compelling).

It’s plausible that teams are behaving suboptimally due to risk aversion - a common cognitive bias that’s shown up elsewhere in sports as well (i.e. in football, going for it on 4th down).

Energy Expenditure

One additional point that coaches might take into consideration is energy expenditure. Suppose ‘crashing the boards’ on a missed shot increases your net point differential in the game by an expected 0.15. Is that worth the extra energy that your team expends going after the rebound?

First, any time you crash the boards, you run the risk of wasting energy if the shot goes in. Consider, then, that 3-pointers are high-efficiency, low-probability shots. It follows since 3-pointers are less likely to go in than a regular shot, crashing after a 3 point attempt is less likely to involve wasted energy.

Rebound Rates by Shot Distance

In 2012 Sloan paper “Deconstructing the Rebound with Optical Tracking Data”, Maheswaran et. al finds missed shot attempts from close to the basket (36%) and from beyond the three-point arc (25.5%) have the highest offensive rebound rates, while missed mid-range shots (21.5%) have the lowest.

As Maheswaran et. al notes, this further increases the value of 3-pointers and close-range 2’s: they are not just efficient shots, they may also be more conducive to grabbing offensive rebounds.

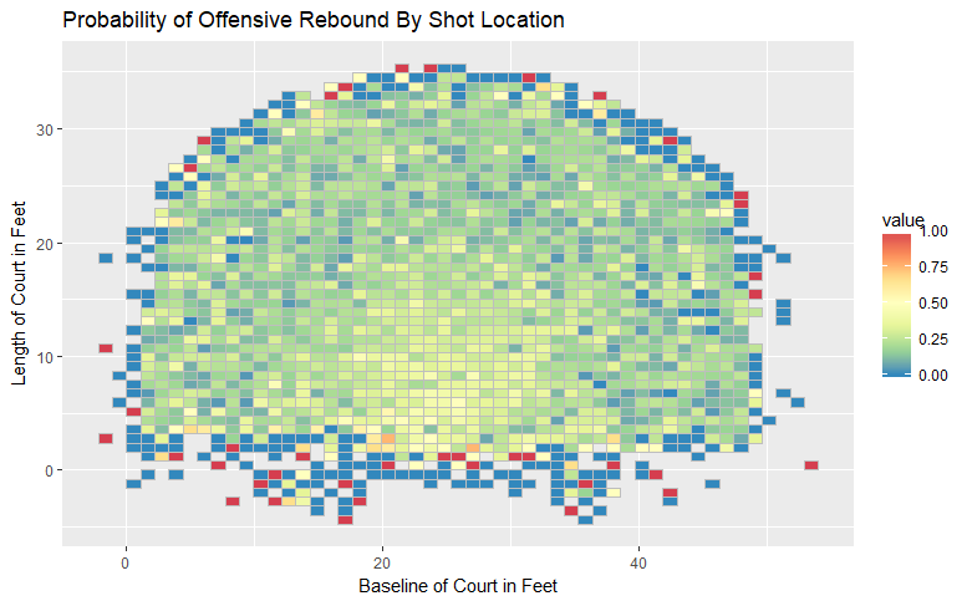

In repeating this study on 2015-2016 NBA data, I was not able to entirely reproduce the same results. My results are below:

| Distance of Missed Shot | Sample Size | Offensive Rebound Rate |

|---|---|---|

| All 3’s | 17555 | 18.14% |

| All 2’s greater than 15 feet | 12474 | 18.85% |

| Between 10 and 15 feet | 5739 | 23.00% |

| Between 6 and 10 feet | 6993 | 28.90% |

| Under 6 feet | 6758 | 35.38% |

Unlike with Maheswaran’s study, missed 3-pointers did not result in an offensive rebound more often than a missed midrange shot. However, close-range shots did still have the highest offensive rebound rate. Here is a crude heat map for my data showing offensive rebounding rate by shot location. The bottom center area is the basket.

Note none of this necessarily implies it is more difficult to grab offensive rebounds off missed 3’s (i.e. correlation / causation) - just that offensive rebounding rates have been lower, the further one gets from the basket (maybe teams go after offensive rebounds less off missed 3’s since it expends more energy).

Takeaways

If you felt like the previous sections were only tangentially related - you are not wrong! My intention in this post wasn’t so much to present a cohesive argument as it was to highlight various ideas to consider when evaluating offensive rebound strategy. If you like modeling, or are doing a project related to sports analytics, any one of these sections could be fruitful for further exploration.

To summarize the post, there is a lot of evidence that suggests offensive rebounds should be more valuable to high-effiency teams (teams that prefer shooting 3’s and close-range 2’s):

- Intuition / logic suggests teams with high relative offensive efficiencies should value offensive rebounds more.

- Data suggests teams are not crashing the boards enough - possibly out of risk aversion. Wiens et. al estimates if a team switched from the least optimal to ‘most optimal’ board crashing strategy, it would equate to a widening of roughly 4 points in point differential per game

- Data suggests that offensive rebound rates are highest for close-range two’s

- Wasted energy expenditure from crashing the boards on made shots is least when crashing on 3-point attempts

What’s unclear, at least to me, is how much more valuable offensive rebounds are for, say the Rockets versus the Timberwolves. Quantifying how much more valuable an offensive rebound is to a Morey-Ball type team would give insight as to whether playing Morey-Ball warrants a custom offensive rebounding strategy:

Other offensive rebounding takeaways unrelated to 3-point shooting:

- Logic / intuition suggests the value of an offensive rebound differs based on who you play

- Data suggests offensive rebound possessions are worth more than regular possessions

- Data does not suggest the value of an offensive rebound should differ by where you shoot from; i.e. offensive rebounds off short-range shots do not have a significantly higher points per possession than offensive rebounds off missed 3’s